Abdulrazak Gurnah Quotes…The Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded to the novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah “for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents”.

Born in 1948 on the island of Zanzibar off the coast of East Africa, Gurnah, came to Britain as a student in 1968. Now, he teaches literature at the University of Kent. He is associate editor of the journal Wasafiri.

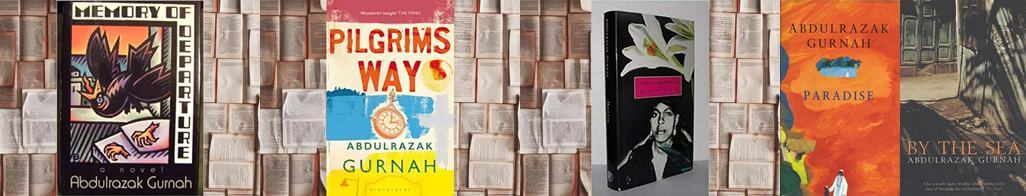

Gurnah, who grew up on the island of Zanzibar but arrived in England as a refugee in the 1960s, has published ten novels as well as a number of short stories. The Nobel committee said that “the theme of the refugee’s disruption runs throughout his work”.

Nobel prize laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah’s dedication to truth and his aversion to simplification are striking. His novels recoil from stereotypical descriptions and open our gaze to a culturally diversified East Africa unfamiliar to many in other parts of the world.

Abdulrazak Gurnah lives in Brighton, East Sussex. His latest novels are Desertion (2005), shortlisted for a 2006 Commonwealth Writers Prize, and The Last Gift (2011). In 2007 he edited The Cambridge Companion to Salman Rushdie.

Abdulrazak Gurnah Quotes

“Sometimes I think it is my fate to live in the wreckage and confusion of crumbling houses.”

Abdulrazak Gurnah, By the Sea

“Respect yourself and others will come to respect you. That is true about all of us, but especially true about women. That is the meaning of honour.”

Abdulrazak Gurnah, Paradise

“That’s the way life takes us,’ Elleke once said. ‘It takes us like this, then it turns us over and takes us like that.’ What she didn’t say was that through it all we manage to cling to something that makes sense.”

― Abdulrazak Gurnah, By the Sea

“I speak to maps. And sometimes they something back to me. This is not as strange as it sounds, nor is it an unheard of thing. Before maps, the world was limitless. It was maps that gave it shape and made it seem like territory, like something that could be possessed, not just laid waste and plundered. Maps made places on the edges of the imagination seem graspable and placable.”

Abdulrazak Gurnah, By the Sea

“For millions of people, she could hear him say with thattremulousintensity of his, moving is a moment of ruin and failure, a defeat that is no longer avoidable, a desperate flight, going from bad to worse, from home to homelessness, from citizen to refugee, from living a tolerable or even contented life to vile horror.”

― Abdulrazak Gurnah, The Last Gift

Abdulrazak Gurnah Quotes

(The following is a two-part interview conducted by Anupama Mohan and Sreya M. Datta with Abdulrazak Gurnah, the well-known novelist from Zanzibar, Tanzania, now living in the UK. )

Anupama Mohani: Would you be unhappy if your novels were called “ocean novels” instead of “world literature”? Do you think that world literature is an unsuitable category to convey what oceanic literature/s can?

Abdulrazak Gurnah: I am guessing that by “ocean novels” you mean the connections between littoral cultures which I refer to repeatedly in my writing. I am not certain if this is plausible as a category or form, more likely it is an organising description. What I mean is that if the rationale of the narrative wants to see connections, then the term will work, so its weight is really in the narrative focus rather than in culture or location. As for “world literature,” I cannot overcome the sense that it refers to an attempt by the academic discipline of comparative literature to reposition itself beyond its Eurocentric tradition. I am aware that there is an interest in the idea of a “world literaure from the global south,” and while I sympathise with the

Sreya M. Datta: Many of your novels, Professor Gurnah, deal with the condition of asylum seeking, something which you vividly show in the immigration scene in By The Sea. In Desertion, however, we find a more subtle explanation of the theme of asylum when Amin advises his younger brother Rashid to never let grief and homesickness envelop him, and to carry on in his life abroad. How do you relay postcolonial aspiration not as a choice, but as coercion, even though the choice to emigrate may be technically unforced? How does this tie in with your philosophy of migration in an asymmetrical world system?

Abdulrazak Gurnah: By the Sea is about asylum from several perspectives, Saleh Omar, Latif, Jan and Elleke, in most cases, being driven by events. Desertion is concerned with the choices people make, or at least what appears as choice. I don’t think it is concerned with asylum as that act of desperation in crisis. Rashid chooses to leave, is indeed passionate to leave, and only later realises what he has given up or lost. Amin has selected himself as the faithful one and cannot leave. His advice to Rashid to persevere is therefore part of his sense of himself as a man of faith and as also rising to his brother’s need. Both are novels which reflect on the consequences of colonialism, which is what I assume you mean by “an asymmetrical world system.” They are also novels of how people sustain themselves and their ways despite the disruption colonialism brought to their lives.

Sreya M. Datta: Your novels are distinctive in their absence of comic relief, or even moments of happiness and light-heartedness, which are not overshadowed by the prospect of impending despair or paralysing loneliness. Would you agree? Is this kind of melancholia a deliberate or functional novelistic strategy?

Abdulrazak Gurnah: I would not agree about the absence of what you call “comic relief.” No doubt you have a different idea of comedy from me, but I think there is comedy both in events as well as in the language. As for the overshadow of pain and loneliness, I believe that is the condition of human existence.

Anupama Mohani: In some familiar way, your writing reminds me of Conrad, who, really, in all his oeuvre had one single tale in mind to tell, and in story after story, he refined and honed that one single tale: the tale of a haunted man trying to escape his past, but in vain. The plot is merely incidental to Conrad’s works; the how and why occupies the reader almost completely. Your novels too point me towards the idea that perhaps in all your work, you are really impelled by one spectral tale which you want to refine, nuance, parse until … well, until some goal you have in mind is achieved. Would you be happy with such a characterization? Could you elaborate how your narrative focus has evolved in your novels?

Abdulrazak Gurnah: I don’t know if there is “one spectral tale” I want to refine; I am sure there is more than one. I have referred above to the choices people make to stay or to leave. I have written repeatedly about that, also about the experience of living on arrival in Europe. So there is one focus of what I write about: belonging, rupture, dislocation. Perhaps that is already more than one focus, and within those three, there are already many other issues to do with loss and pain and recovery. I write about the resourcefulness with which people engage with these experiences.

Sreya M. Datta: In your latest novel, Gravel Heart, the sea appears to almost fade into the background as you concentrate on family history and relationships. Salim’s relationship with his father Masud governs the direction of the novel. Moreover, Salim does return home briefly, a choice that seems closed for most of your other characters. How do you relate histories of the family with histories of the ocean, the two themes you develop continuously in all your novels?

Abdulrazak Gurnah: Salim returns to re-engage with his father, but the choice to return is not closed to others I have written about. The narrator of Admiring Silence returns. Rashid at the end of Desertion is contemplating a return. The important part of their experiences is the leaving or the rupture with their lives which makes the return a complicated choice. In the case of asylum seekers, the return is not always possible for legal reasons or from fear of violence. I would have said that Gravel Heart was also, and in an important way, about power and its capacity to distort the intimate reaches of relationships.

Sreya M. Datta: In some of your non-fiction essays, you have spoken about how your journey towards becoming an author has been a complicated one. In “Writing & Place,” for instance, you have spoken about how writing was something you “stumbled into rather than the fulfillment of a plan.” You speak about the time you left home for England and started writing out of the sense of a vivid memory you had of Zanzibar in contrast to the “weightless existence” of your early years in a new country. In “Learning to Read,” you write about how the contradictory cultural influences of your childhood in Malindi fed into your overall cultural vision that had to actively navigate contradictions and complications within itself, which, in a sense, means that you were already “writing” before you formally started out as an author. Is this still your sense of your journey towards authorship or has it undergone any degree of revision in retrospect? Could you tell us a bit more about whether this complicated journey also translates into some of the complicated journeys your characters embark upon?

Abdulrazak Gurnah: It has not undergone revision in retrospect. It still seems an adequate description of what you call “my journey towards authorship.” Perhaps I would not have used that phrase but something like “the process of arriving at writing.” I write about complicated journeys as a way of demonstrating the complex interconnectedness of experience, biographies and cultures.

Sreya M. Datta: Could you talk a bit about your latest novel, Gravel Heart? The epigraph is a quote from Abu Said Ahmad ibn Isa-al-Kharraz which says: “The beginning of love is the recollection of blessings.” Why did you choose to begin with this? Does it relate, in any way, to Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, where the title of the novel comes from? How do you envision intimacy in your works?

Abdulrazak Gurnah: It seems to me the epigraph speaks for itself in a novel that has recollection as a central idea. I liked the enigmatic imperative of the advice it offers, which to elaborate on would be to narrow its meaning. Measure for Measure is also an enigmatic play in some senses but above all, it is about the abuse of a rhetoric of righteousness for self-gratification. In that sense, it is the other side of the sufi’s exhortation, the other side of the coin that the novel spins. I envision intimacy as it appears in the novels, as a continuous process of engagement and negotiation.

Anupama Mohani: Do you carry out any kind of specific historical research when you are writing, say, about the Zanzibar revolution or its aftermath in your novels? Or do you write from memory, or from a sense of events as they happened in the past? Would you say that your novels are impressions rather than realistic portraits of East African life?

Abdulrazak Gurnah: The ground my novels cover has been profoundly interesting to me throughout my life and so in a way I am always researching the material. There is always a need to check or to read in more detail about specific moments, but I write about what I know and care about. I am not sure why you position “impressions rather than realistic portraits” as if they are polarities or contradictory processes. I imagine that fiction unavoidably does both.

Anupama Mohani: Finally, given the vitality of the littoral and regional in your works, how do you see your work vis-à-vis postcolonial studies? In what ways does your scholarly work intersect with and/or challenge your creative work? Naipaul (in)famously said that he chose to be a full-time writer because any other profession would have killed him as a writer. I wondered, therefore, how your twin roles as writer and academic interplay.

Abdulrazak Gurnah: The value of the postcolonial idea as a discursive concept is appealing to me because it allows me to see common ground between writings from different cultures and histories. It is a much more demanding methodology than it might seem if practised without an adequate interest in context. I found no conflict in the roles of academic and writer. They were quite unlike activities, and if anything were mutually beneficial in a small way.

Great for the achievement